Apologies to Stephen King: Kubrick’s The Shining Shows What the Novel Could Only Tell

Kubrick knew what King couldn’t show: the scariest monster is a father with no way out.

I run a Plex server. Every October, it transforms. I load it with Halloween collections — goofy staples like Hocus Pocus, a rotation of slashers, the serious canon of horror classics. This year more friends are on it, which is fun, but honestly, I’d do it even if it were just me. Because for me October isn’t October until I put on The Shining.

I’ve seen it more times than I can count, and it still terrifies me. Not because of the hedge maze, or the elevators of blood, or even the twins in the hallway. Those are window dressing. What makes it terrifying is Nicholson — Jack Torrance — maybe the most accurate portrait of a father as monster ever put on film.

And here’s where I have to pause and say: apologies to Stephen King. He hated Kubrick’s adaptation. Said it was cold. Said Jack was crazy from the first frame. Said Wendy was reduced to a shrieking prop. In the ’90s he even wrote the teleplay for Stephen King’s The Shining, directed by Mick Garris, which stuck closer to his novel. He said he preferred that version. I’ve tried three years in a row to sit through it. I can’t. Kubrick’s film endures because what King thought was a flaw — the lack of agency, the coldness — Kubrick turned into the point.

The Facade (Already White-Knuckling)

From the very beginning — even in the car on the way to the hotel — Jack’s performance isn’t warmth. It’s curt, dismissive, slightly hostile. Danny says he’s hungry, and instead of comfort, Jack snaps back with a reprimand. The best he can do as a father is scold. Wendy, by contrast, reassures Danny they’ll eat soon. That little triangle in the car tells you everything: Wendy is the buffer, Jack is the disciplinarian, and Danny absorbs the tension.

This is Nicholson’s brilliance. Even Jack’s facade — his version of “trying to be normal” — is already shot through with irritation. Sobriety isn’t freedom here, it’s white-knuckling. He’s been on the wagon five miserable months, and it shows. The hostility is always there, right under the skin. The hotel doesn’t have to create it. It only has to strip away the last shred of restraint.

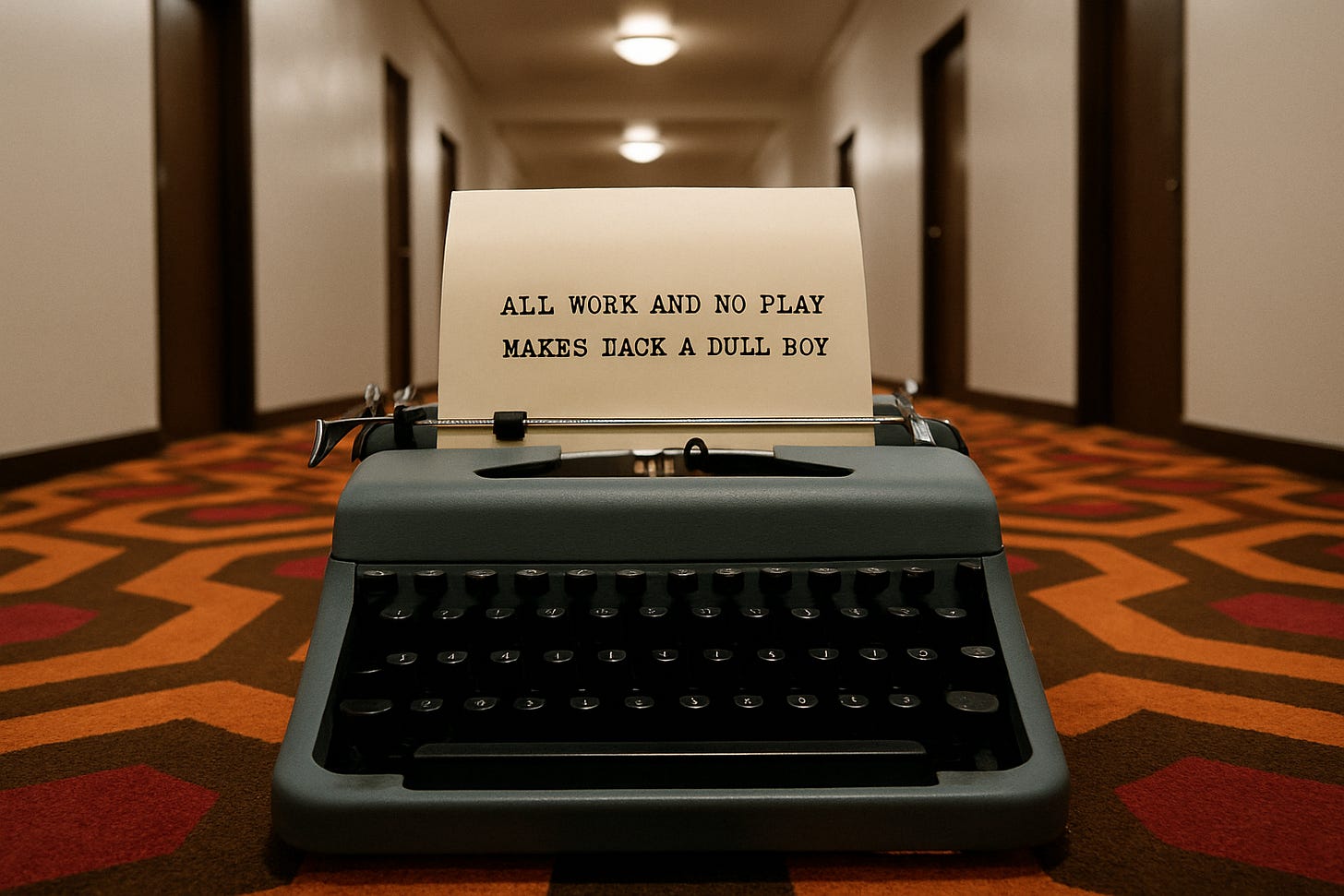

The Typewriter (Drunk Without the Drink)

Then there’s the typewriter scene. Wendy interrupts him, and he just detonates. “Whenever you come in here and you hear me typing…” It’s drunk rage, sharp and venomous, even though he hasn’t touched a drop. And the cruel joke? He isn’t writing anything at all. Later, we’ll see it: All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy. Page after page of gibberish. His “work” is a sham, and the strain of pretending wears him down. When his focus breaks, the mask breaks. And the hotel slips in through the cracks.

The First Drink

And then Lloyd appears. The empty bar, suddenly glowing, suddenly full. Jack lifts a glass and says, “Here’s to five miserable months on the wagon.” It’s a confession disguised as a toast. Sobriety wasn’t noble; it was suffering. And with that drink in his hand, Nicholson relaxes. He’s smoother, looser, more himself. This isn’t possession. This is relapse. And here’s the cruelest part: Jack Torrance is never more at ease than when he’s drinking.

Dissociation

Right after that, Wendy confronts him about Danny. And Jack looks wasted. Slurred speech, slack face, pure hostility. Whether the liquor is “real” doesn’t matter. It’s real to him. And that’s all it takes.

The Green Room

Then Room 237. The woman in the tub. Desire that curdles into horror. Jack stumbles out of the room hollow-eyed, vacant. This is the hinge. Not just relapse anymore — possession. Jack’s gone.

The Bathroom with Grady

And then Kubrick makes it explicit. Jack meets Delbert Grady in the red bathroom. “You chopped your wife and daughters into little bits,” Jack says. And Grady doesn’t deny it. He reframes it: “I corrected them, sir.” Domestic violence, repackaged as duty.

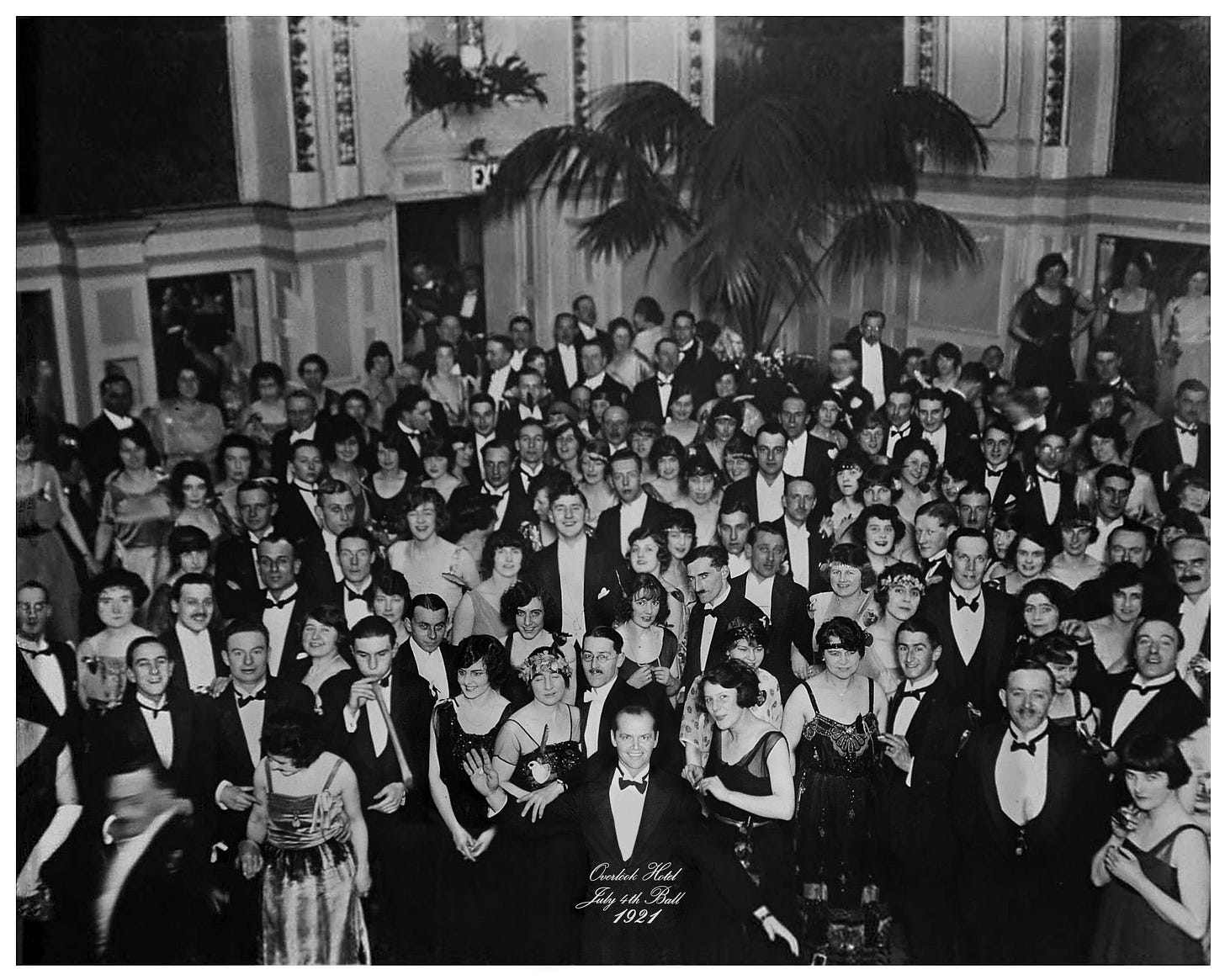

Then comes the line that collapses everything: “You’ve always been the caretaker. I should know, sir. I’ve always been here.”

This isn’t Jack becoming possessed. It’s Jack being told he’s always belonged here. The eternal role. The father who destroys his family, again and again.

The Pantry

For a moment, Wendy seems to win. She knocks him out, drags him to the pantry, latches the door. He’s trapped.

But then the voice returns. Grady. Calm, steady, instructing him. And the door unlatches by itself.

That’s the moment Kubrick refuses to let you rationalize. Up to now, you could argue it’s all madness — hallucinations, drunk rage, a man unraveling. But no delusion opens a locked door from the outside. That’s the hotel. That’s the supernatural. And from then on, Jack is finished.

The Descent

The finale is nightmare fuel. Jack with the axe, chasing Wendy and Danny through the hotel, through the maze, grin stretched wide. The facade is obliterated. No fake civility, no discipline at the typewriter. He’s free — and freedom here means annihilation.

And that’s exactly why King hated it.

Kubrick vs. King

King wanted a tragic arc. A decent man undone by the hotel, corrupted step by step. Kubrick gave us no arc at all. No redemption. No agency. Wendy doesn’t “save the day.” Danny doesn’t defeat the evil. They just survive. And Jack isn’t a good man lost. He’s a bad man revealed.

That’s the coldness King despised. But Kubrick knew: that coldness is the point.

The Eternal Return

Because once you strip away choice, what’s left is the loop. Jack has always been the caretaker. The hotel isn’t haunted by ghosts; it’s haunted by cycles. Fathers terrorizing their families. Violence repeating, over and over.

Hell isn’t fire and brimstone. Hell is being locked in that role forever.

Or Maybe…

But maybe that’s too bleak. Because Jack does die. Frozen in the maze, pathetic, beaten by his own incompetence. Wendy and Danny do make it out alive. Maybe that’s the story — a mother clawing back just enough strength to protect her son. Maybe it’s proof the cycle can break.

Or maybe it’s just a haunted house flick. Sometimes October doesn’t need a thesis. Sometimes you just want a scare.

And that’s Kubrick’s genius. The Shining holds all of it at once. It’s addiction. It’s possession. It’s the eternal return. It’s survival. It’s just a damn good horror movie. However you read it, it never lets you out clean. It keeps you circling.

Closing

That’s why I keep coming back. Every October, my Plex server fills up with the usual horror lineup, but The Shining is always the centerpiece. Because every time I put it on, it’s something different. Sometimes it’s about addiction. Sometimes it’s possession. Sometimes it’s a cycle that never ends. Sometimes it’s a mother and son breaking free.

And maybe that’s the point. It doesn’t settle. It doesn’t close. It just keeps pulling you back.

That’s the real Overlook Hotel.

And that’s why I’ll keep pressing play every October — right after Hocus Pocus.