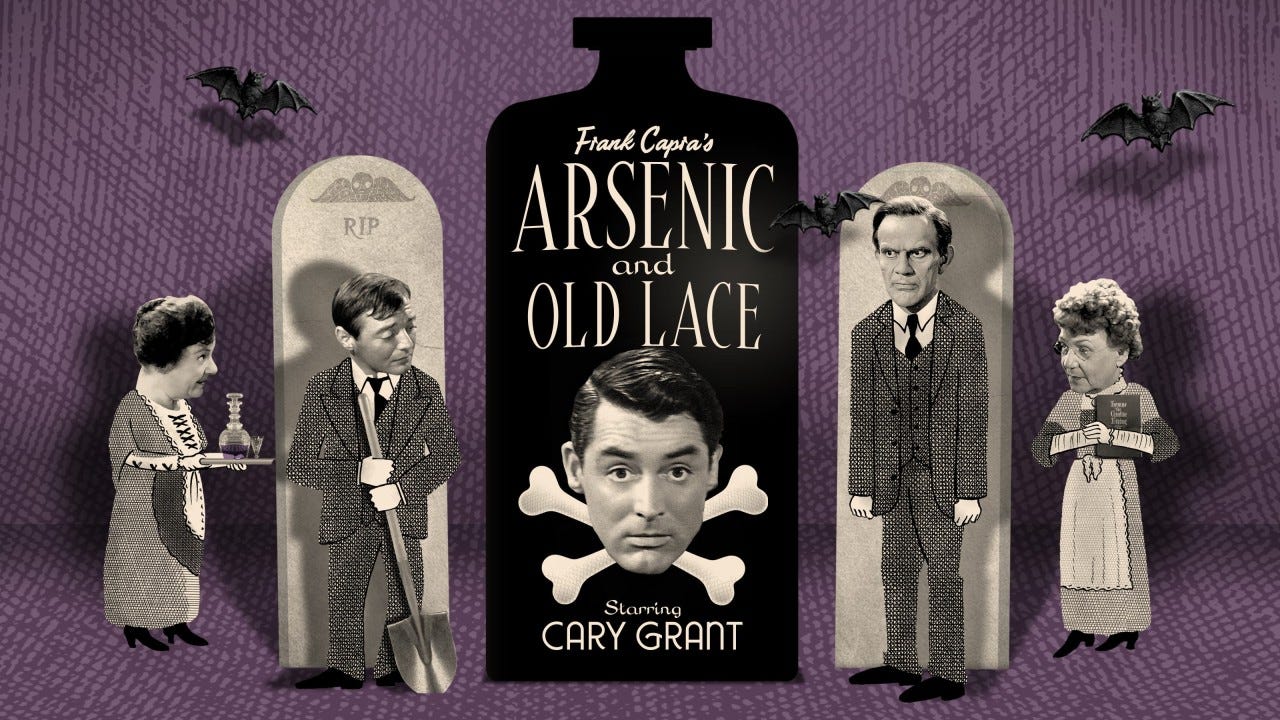

How a 1944 Screwball Comedy Turned Into My Halloween Ritual

Frank Capra’s Arsenic and Old Lace isn’t just a movie — it’s a ghost of Broadway, trapped on film.

I have a friend.

She’s watching Arsenic and Old Lace tonight.

And so am I.

I know she’s watching it because it’s her tradition — and it’s a tradition she passed on to me. She’s the one who introduced me to this movie and, really, to my deeper love of classic Hollywood and theater, which this absolutely is.

There’s no coordination, no plan, no reminder. At some point during the night, she presses play, and I do too. The same film, the same glow, the same laughter, shared across the quiet.

She’s always loved the golden age — that whole era where style met timing, where everything was performance. She’s that part of me that still loves the shape of old light, the confidence of an era that believed in pace. And so, every October 31st, we share this small act of keeping it alive.

And make no mistake — Arsenic and Old Lace is a Halloween movie.

Not a curiosity, not an offbeat pick. It takes place on Halloween night in Brooklyn. Cool air. Rustling leaves. A bugle upstairs and a secret under the window seat. Two sweet old ladies serving poisoned wine with a smile. It’s gothic and farcical, cozy and unhinged — the perfect Halloween contradiction.

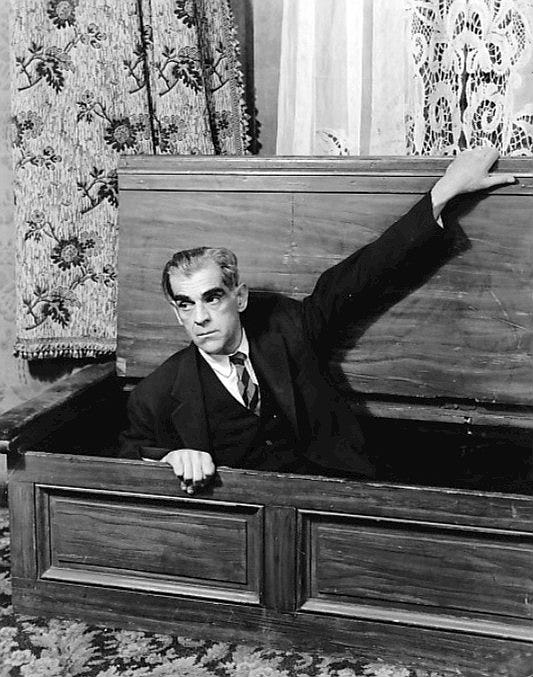

The story began on Broadway in 1941, written by Joseph Kesselring and produced by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse. It ran for more than 1,400 performances at the Fulton Theatre — an instant hit. Boris Karloff, fresh from Frankenstein, originated the role of Jonathan Brewster, the murderous nephew whose face was said to “look like Boris Karloff.” That in-joke became legend. When Frank Capra adapted the play for Warner Bros., he kept almost the entire stage cast — except Karloff, who was contractually bound to keep performing on Broadway. Capra even delayed the film’s release until the play’s run finished, out of respect for the production still filling seats on 42nd Street.

And into that world stepped Cary Grant, as Mortimer Brewster — a role meant to feel like a Broadway leading man caught inside a mad farce. Grant was perfect for it.

He’s a storm in this film — completely unrestrained, all motion and disbelief. He flails, folds, argues with reality. His body tells half the story before the words arrive. There’s a scene where he’s tied to a chair, and even then he turns it into a piece of choreography.

Grant began his career as an acrobat in vaudeville, performing flips, balancing acts, and stilt-walking. You can still see that lineage here — the control, the rhythm, the way he moves like someone who understands gravity intimately. Over the years he refined that energy into charm, but this might be the last time he truly let his acrobat’s body drive the performance. It’s physical, chaotic, funny — a farewell, maybe, to that earlier version of himself.

The movie’s rhythm comes from that same physical pulse. It’s all timing. Every line lands a half-beat early. Jokes overlap. Tension rides the edge of panic. The camera doesn’t cut to keep things moving — the people do. Capra built it like stagecraft: long takes, slow pans, wide shots that hold while the actors fill every inch of the set.

And then there’s “Teddy Roosevelt” Brewster, charging through the house like punctuation. He isn’t just comic relief; he’s the metronome. Every entrance resets the room, turns fear into laughter, and resets the tempo again.

When I learned that much of the cast came directly from the original Broadway company — Josephine Hull, Jean Adair, John Alexander — it all clicked. Of course it feels that way — big, alive, projected. These weren’t film actors yet; they were stage performers still playing to the back of the house. You can almost sense the proscenium just beyond the camera.

That’s what makes this film special. Theater isn’t supposed to last. It exists, it vanishes, and the next night is something new. But this — this one stayed. Capra managed to trap a performance that should have evaporated. It’s why Arsenic and Old Lace still feels kinetic instead of quaint: it’s not a movie about theater; it’s theater, caught mid-breath.

If you close your eyes while watching, you can almost place yourself there: eight rows back at the Fulton Theatre, 1941. The orchestra tuning fades. The house lights dim. The audience leans forward. And then Cary Grant steps into the glow, already unraveling, already halfway to panic.

It’s alive. It still is.

If you haven’t seen it recently — or ever — Criterion released a 4K restoration in October 2022, and it’s stunning. Sharp, patient, luminous. You can see the grain of the film, the brush of stage lighting baked into every frame. If they’re paying attention, you should be too.

So tonight, maybe press play too.

Make it your ritual. Share it with a friend.

Let the film move the way it wants to — fast, funny, theatrical, alive.

And somewhere in the middle of it, maybe you’ll feel what we feel: that sense that you’re eight rows back in 1941, watching a Broadway night that somehow never ended.

If you’re enjoying this kind of piece — slower, seasonal, film-soaked — tap the heart or drop a comment.

Tell me your own Halloween ritual, or the movie you return to every year. I read every one.

I'm going to have to check this out! I'm not sure I've ever seen it!